Making the Four Old Gods

Note: This post contains light spoilers for Fire Emblem: Fates, and gameplay spoilers for The Four Old Gods.

I participated in Enbyjam in August, 2016, pretty much entirely on a whim: I wanted to make a game, and there happened to be a jam running, so I used the jam’s running time as a deadline. It gave me a week (and change - technically 9 days) to make a game. And decided to make a strategy game. You can play it here.

I will be the first to say that a strategy game is probably not the best choice for a game jam. There are a lot of pieces, and it requires a lot of code, art, and playtesting. I went into it fully expecting to fail, like the last three times I tried to make a strategy game for a game jam.

But somehow, I made it. It’s a short strategy game, more like a strategy RPG, that can be beaten within an hour, but it’s playable and I’ve heard it’s quite fun.

I think that this project was only possible because I’d failed at making so many strategy games before. I had a lot of ideas and assets left over from those projects, which I was able to incorporate into this game without too much overhead.

This is a series of notes which may give some insight into the process I used, and the technologies behind them.

The game was made in Game Maker: Studio.

System & Pathfinding

I started the game with a particular mechanic in mind. Specifically, I was trying to code a prototype for a Real-time with pause strategy game, where the action would all move in real time, but could be stopped at any point to give orders or to look over the field.

I wanted the game to avoid having the incredible time pressure / actions per second mayhem of real-time strategy games, while avoiding having to code a turn-based system. Also, this was a system I hadn’t seen very often, so I wanted to try it out to see how fun it could be.

I started with programming those mechanics, by implementing a very simple global pause, and giving each in-game moving object a simple state machine.

The pause amounted to a global variable, and the state machine a local variable ‘state’ created in the object, and a switch statement in the step event, like so:

switch (state):

case states.free:

// do movement

break;

case states.pause:

// nothing but animations

break;

This was the part where previous experience was very helpful. I was able to code this pause and state machine very quickly, and move on to implementing pathfinding.

I used A* for pathfinding, which is implemented natively in Game Maker. The system calculated a path using a 48x48 pixel grid, and tried to ‘cut corners’ whenever possible: If there were no collisions on the line between the object and the point after the next turn on the path, it would move directly to that point rather than follow the path.

Mouse selection was also done by end of day. I decided early on to limit the number of playable units to make the game more manageable, and that meant that having a rectangle selection for units was unnecessary. Units were selected by clicking on them.

By the end of the day, I had a good engine for the game, where units could be selected, moved to the mouse while avoiding walls, and the game could be paused at any time.

Map Design

I figured that there would only be one level, so the objective of the game had to be fairly easy to understand. From the few strategy games I played, I had a short list of the typical objectives in a strategy game level:

- Defeat all enemies

- Destroy some important target (enemy bases, energy source, etc.)

- Move your unit(s) from point A to point B

- Defend a location / object / character for an amount of time

Admittedly, this list is almost entirely from Fire Emblem. I don’t actually play many strategy games.

Anyway, I decided to use the ‘defend’ objective, for a variety of reasons. It allowed me to figure out exactly how long an individual game should last, made for fairly simple AI coding (since the enemy wouldn’t have to defend anything on their side), and finally, I’d managed to come up with a short plot that fit nicely with that goal.

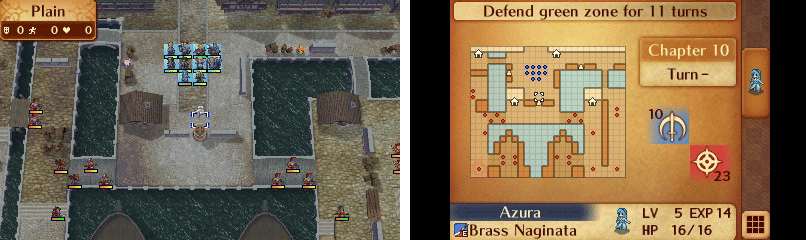

At any rate, with a defend objective, the map had to make that objective fun somehow. I took another page out of Fire Emblem, specifically how Chapter 10 in Fire Emblem Fates: Conquest was designed. Without going into too much detail, in that level, you and your small army have to keep the enemy from reaching the city at the Northern end of the map. There are four main paths to the city separated by waterways, each populated with different kinds of enemies, as well as a few fliers who can ignore obstacles. Near the end of the level, the enemy drains the water, allowing the remaining enemies to swarm you from all sides.

It was a lot of fun to play. The player’s army wasn’t so big that you could easily defend all four routes without breaking a sweat, so the one healer was often zipping back and forth. It was more tactically advantageous for one group to charge ahead and thin out the enemy, so that you wouldn’t be swarmed at all four paths at the same time.

I wasn’t going to have time to implement any kind of map change or destruction, but the concept of having different paths that the enemy could take was interesting. There’s a lot of choice there, in deciding who should defend which path and when. Also, having narrow paths (chokepoints) help make the difficulty manageable, as relatively small numbers of units can hold back a large number of enemies temporarily while the player fortifies defenses.

Those ideas ultimately factored into how I designed the map. There are a few ‘rooms’ with narrow entrances that act as chokepoints, and four different paths to the Relic that needs to be defended.

The map of the Four Old Gods has four spawn points for enemies, one on each corner. Since the Relic isn’t in the center of the map, it meant that the enemies from each spawn point would reach it in a different amount of time. So at the beginning of the map, where difficulty should be lower, the spawn points furthest away from the Relic were used, and the player given a lot of time to prepare. As the level goes on and gets more difficult, enemies start spawning from multiple spawn points, forcing the player to creatively use their units.

A side-effect of this map design was that it really felt like the player was being assaulted by a force they had to continually defend against, since by the end, they would be attacked from all sides.

Character Design & Art

By this point, I’d had a general idea of the plot and characters, and that I’d only have four of them. Specifically, a classic RPG party of sorts: a slow powerhouse, a ranged attacker, a fast and frail unit, and a healer.

I decided that stats and mechanics of combat would follow RPGs loosely and simply as possible. All characters only had ranged attacks, mainly because that required fewer animations and were easier to program. As a result, I decided on the following stats:

- Power: the amount of damage the character does per attack (or heals, in the healer’s case)

- Armor: Damage reduction. The damage formula was a strict

max(attacker.power - defender.armor, 1)to keep things simple. - Speed: How quickly the character moved.

- Range: How far the character’s attacks could reach.

More of the stats were about movement than the actual interactions of combat, which is intentional given that this was a game very much about character placement. The AI was designed to be very simple as well, so that if an enemy was in the character’s Range, they’d launch a shot at them. For multiple enemies, the one closest to the character currently.

The characters are all named after the Four Chinese constellations. The plot was an existing one I hadn’t done much with, so the hard work of figuring out what the characters and world looked like had been done, and what remained was actually creating the art assets.

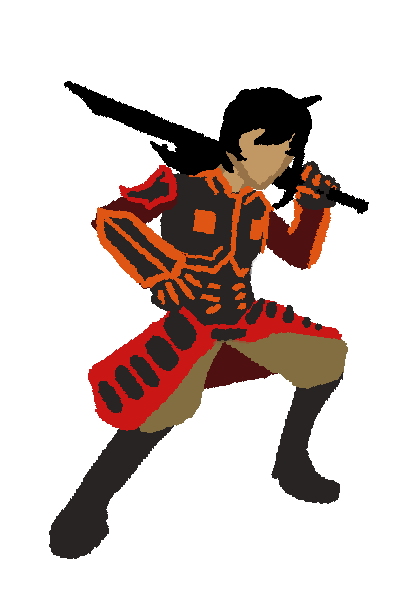

I drew the art freehand in Photoshop, using a pencil for hard edges, and general blocks of color without shading. This was then scaled down to game size, and ended up looking like pixel art.

Vermillion Bird’s sprite, at the resolution it was drawn.

Vermillion Bird’s sprite, at the resolution it was drawn.

Vermillion Bird’s sprite, in-game size.

Vermillion Bird’s sprite, in-game size.

Portraits were drawn in the same way, though with only two colors (both for style, since the characters all had a color in their name…and also because it’s faster). The portraits were not scaled down as the in-game character art was, though.

Enemies & AI

There was only one type of enemy, for time’s sake. All it would do was to select the Relic as its target, and move towards and attack that target. It would also change its target to any unit that attacked it, and could theoretically chase player units around if they provoked it. This behavior was added to make the game beatable - if the enemies ignored the players, because of the way my collisions worked, there was no real way to stop them from reaching the Relic and overwhelming the player with sheer numbers.

This is a rough version of the AI:

// create

target = relic

// step

if (distance_to_object(target) < range) {

// attack

}

else {

move_path(speed, target.x, target.y)

}

// collision with enemy attack

target = other.owner

The enemies used the same pathfinding and attack algorithm as the players, so didn’t end up costing too much time to program. Spawning was determined by a timeline, where after x seconds of ingame time (pausing stopped the timer), a set number of enemies would spawn at one of the spawn points, at two-second intervals.

This is definitely an area where the game could be expanded in the future, as I could envision multiple enemy types making the game more tactically deep. Enemies with different move speeds would need to be dealt with differently, or enemies that could bypass certain obstacles, etc.

Collisions are natively available in Game Maker, so that’s nice as well. Since the attacks would usually be destroyed upon collision with an enemy, and the pathfinding handled walls, I didn’t really need to implement any kind of physics.

End Notes

There’s a lot I didn’t get into, specifically audio (which was made within a single day) and things like screen transitions and text. At some point, I hope to expand this game – or at least explore the mechanics behind this game some more, and create a full-length project out of it.