Making Starlight

Note: This post contains spoilers for Starlight, if you care about that. You can play Starlight here first if you want. It’s free, and has a playtime of about 10 minutes.

I was introduced to LOWREZJAM by way of a friend, and decided early on not to participate on the account of having finals. Unfortunately, I have a persistent game jam problem, and joined anyway.

I made Starlight over the course of five days using Game Maker. I say five days, but it actually was much longer than that; it was five days of actual development made possible by my familiarity with Game Maker, by the fact that the ideas had been rolling around in my head for weeks already.

To my surprise, the game turned out much better than expected. It won 10th place in the jam.

This is just a few notes on its conception.

A Strategy Game

The core concept of LOWREZJAM is that the entire game needs to fit in a 64x64 pixel square (that can be scaled up to be a more reasonable screen size).

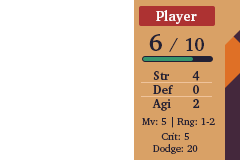

When I first decided to join LOWREZJAM, I wanted to make a strategy game. A turn-based strategy game. I had been binge-playing Fire Emblem, and wanted to do something like that, stripped down to its absolute basics. I even had (pre-existing) mockups of what I wanted the UI to be like:

There were some immediate problems. For one, this mockup was 240x160 pixels, and shrinking it down to 64x64 was going to make everything absolutely unreadable. For two, I quickly realized that trying to make a full-blown strategy game would take me far too much time with finals in the way.

Initial Concept

The next game concept I tried was the one that I ended up using. (The nice/awful thing about game development is that I get so many ideas that I can’t use in current projects, which are stored away in my notes for when game jams roll around.) The idea was a space exploration game where you get from one star to another, by clicking on nearby planets and ‘chaining’ your way to your destination.

If you’ve played Spore ever, it’s pretty much the mechanic for travel during the space stage.

The original idea also had various hazards that you had to avoid on your travels, and perhaps a time limit. As I started developing the concept, these mechanics stopped making sense (…and would’ve added extra development time), and so were removed.

Very quickly, I decided against making it a pure space exploration game, and decided on creating a more surreal and colorful world (using stars as the waypoints rather than planets). This was a purely cosmetic decision at the time; I’m better at drawing weird land-like environments than I am at drawing the cosmos.

The World

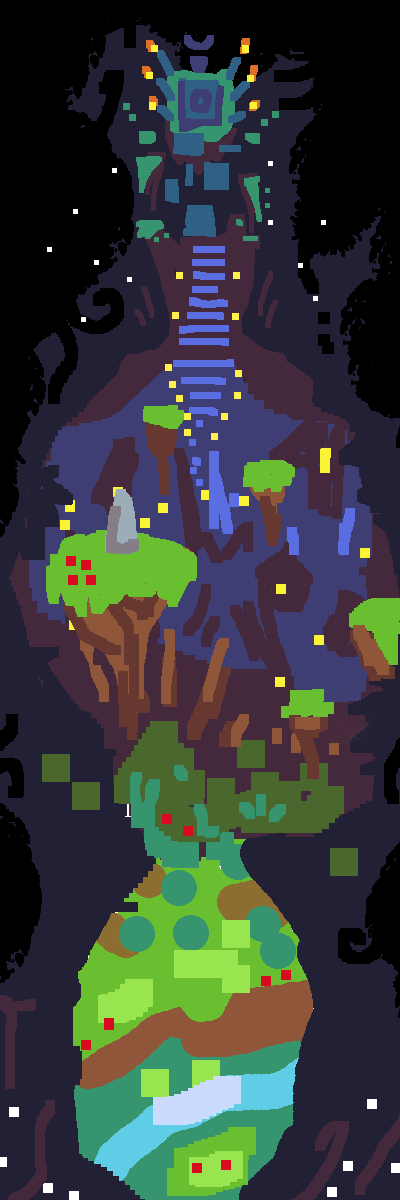

The first part of the game that got finalized was the world: what setting the game took place in, what it would look like, how the player interacted with it (or in this case…didn’t interact with much at all). I ‘painted’ some concept art of the world with my laptop trackpad, mostly just blocking down large areas to get a sense of how it’d progress:

Some design decisions naturally stemmed from that. The world is much longer than it is wide, and you start at the bottom and make your way up. Even before knowing the plot, I arbitrarily decided that the top would be some temple or altar of some sort, that I’d put something to do with candles there. The floating islands were just for fun, and then they became part of the world as well.

Most of the artistic decisions were made on a whim. Why are there floating islands? What’s with the light staircase? The red flowers? That obelisk on the largest island? They don’t serve any major purpose, but are fun to look at.

I was going to refine the concept a bit more before finalizing it, but I liked this sketch so much that for the final pixel art of the world, I simply drew over that rough sketch. The end result in-game looked like this:

Plotting

I don’t know if this is the process that other people take when making games, but I usually can only start writing the narrative for a game once I have a solid concept of the world and the artistic direction. (This is a problem when I’m writing prose - I often have to draw out the characters or a rough sketch of the world before I can figure out the rest of the plot.)

After making the world, I knew this game was going to be a narrative game. I wasn’t sure what else to do with it, and all the little details in the world begged for a reason to explore them.

I decided on two things, with regards to the narrative:

- The main plot would be presented as a poem

- The narrative should be less than 100 words

The story I came up with is about a wandering spirit who travels to the stars on the New Year and lights them up for the coming year. Throughout the course of the game, an unseen person talks to that spirit, about how the people used to worship them, but have since stopped, and how they continue to pray so that the spirit wouldn’t be lonely.

I’m also fairly certain that that synopsis was longer than the text in-game.

I can’t tell you much as to the inspirations behind what became the final plot in game. I think I was inspired by ghosts, I like writing about ghosts a lot. I also like writing about dreams, especially impossible ones. And loneliness. Somehow those all fit together in some way, and fit pretty naturally as well with the theme on stars, so that’s how it all came to be.

Originally, the whole script was going to be delivered in two cutscenes: one at the beginning, and the ending. I ended up splitting it into more pieces mainly for logistical reasons, as only a single line of text could be displayed on screen at once. I thought that very long cutscenes would quickly become boring.

I had no designs in mind for the spirit or the narrator; by virtue of pixel limitations, the spirit’s final appearance was not much more than a head, and honestly, there wasn’t much thought put into it.

Coding

This was the last piece, to my surprise. I’d already drawn and written everything before even touching the code, so there wasn’t any stage of the code where I was using placeholder anything.

Game Maker has a lot of moving and rendering functions already built in, so drawing the world and placing the stars was fairly simple.

The main challenge was actually player movement. I wanted the player to be able to swing across the stars and sort of slowly close in on them, and ended up coding a simple and highly-inaccurate physics system to do so. (It’s embarrassingly bad, to the point that I’m unwilling to reproduce it here.)

The camera moved to follow the player, but not absolutely perfectly: I think the player had to be ~10 pixels off-center before the camera would start moving to catch up. The main rationale behind this design decision was that trying to center the player at all times was giving me motion sickness, due to the swinging, drifting nature of the movement.

The music layering was done by a set of scripts called trackdog. Aside from some weird audio gain issues, I did none of the sound coding myself.

I wrote a simple system to display text and render cutscenes for Starlight, as well as a shader to perform the interesting fades that are used in-game, both of which would take too long to explain here. They’ll likely appear as future blog posts.

Aside from that, Game Maker practically took care of the rest: transitioning between screens, drawing, etc. The title screens and game over / completion screens were created with about 3 lines of code apiece.

If there was anything very surprising about this game, it was that the coding went almost too smoothly, without much in the way of major errors or issues. Part of that was by design: all the mechanics, art, and writing had been cut down to an absolute minimum, so there were less parts that could break, less parts I needed to test. The game itself was short enough to play through that I could test with the actual game rooms, and complete the flow from beginning to end quite easily.

I did make one test room, though: a screen with five stars total on it, just enough to read through all of the storyline cutscenes and make sure they worked.

What worked

- The world and atmosphere. I spent by far the most time on the assets, which worked in my favor. It seems people enjoyed exploring the world, and the narrative, which I’m fairly proud of.

- The simple gameplay. I was worried about this, since it pretty much boils down to ‘click to explore’, but it seemed people enjoyed it. I enjoyed it enough to play through testing, so I guess that should’ve tipped me off.

- The layered music. It was just ‘window dressing’ when I implemented it, but it was something that almost everyone who gave me feedback about the game talked about

Moral of the story? Narrative consistency, art, details, they matter. Games are ultimately experiences, and even simple games are enjoyable if they present a well-designed experience. Individual pieces in-game don’t have to be masterpieces either, as long as they fit together and create a sense of cohesive world (even if they weren’t designed as a cohesive world).

What didn’t quite work out

Honestly, everything came together much better than I expected. Nevertheless, there were things to improve, so much that I made some edits after the jam:

- The star collection. Pretty much the only game mechanic at the time of the jam was that you needed to hit every star to beat the game, and people frequently missed one or two and quit. The second version, ~80% of the stars was enough to see the ending. This was the main point of criticism I got about the game.

- I implemented a small blue arrow that would appear and point towards stars that you hadn’t visited once you collected ~95% of the stars. It was designed to help players who might’ve missed a star or two, but most people ended up missing the arrow entirely. The second version draws attention to the arrow in narrative, though I’m not sure if it helped. I probably should’ve made it bigger.

Other notes

- When designing for a 64x64 pixel screen, you cannot squeeze that many words onto it, no matter what font you use. UI becomes a concern. It was why I had to abandon the strategy game idea.

- You can achieve consistency in pixel art games fairly simply by sticking to a set of colors for the whole game. Consistent shading style matters too, but having a nice, limited color palette does a whole lot already.

Ending thoughts

That’s all I have. This ended up mostly being a design process rather than a proper post-mortem, but that is because of how well it did. Even after processing all the pieces that went right, I’m still surprised at it.

It’s a game, the first fully completed one of mine in 3 years. I’m quite proud of it. You can play it here, if you want.